Open a bag of chips, unbox a frozen lasagna, or unwrap your favorite ice cream bar today, and you might…

Why Do Budweiser and Molson Coors Distributors Keep Losing Their Non-Alcoholic Beverage Brands?

A wave of major acquisitions in the non-alcoholic beverage and snack industry has brought a recurring problem into focus: when a hot brand gets acquired, Budweiser and Molson Coors distributors often lose it. These weren’t just business deals—they were wake-up calls, revealing a pattern that’s hard to ignore.

Despite having some of the most powerful distribution systems in the country, Budweiser (Anheuser-Busch InBev) and Molson Coors distributors seem unable to hold onto the very brands they help build. Dozens of emerging non-alcoholic brands have launched through their beer networks, which are built for moving high-volume product to bars, c-stores, and chains. But once those brands hit critical mass, they leave—usually pulled into the distribution systems of PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, or Keurig Dr Pepper.

So why does this keep happening? And more importantly: why aren’t Budweiser and Molson Coors building stronger systems to keep these brands in-house, even after acquisition?

Why Budweiser and Molson Coors Lose the Brands They Distribute

At the heart of this article is one pressing question: Why aren’t Budweiser and Molson Coors investing in building better distribution systems for non-alcoholic beverage brands?

They already have powerhouse logistics and route-to-market infrastructure. They service thousands of retail and on-premise accounts with precision. So why is it that, time and again, when an up-and-coming non-alcoholic brand catches fire—and is eventually acquired by a larger company—that brand leaves the beer network?

It’s not just about losing the brand. It’s about what that loss represents: missed opportunity, declining relevance, and a reluctance to evolve.

If Budweiser and Molson Coors distributors—and their suppliers—were truly committed to the future of beverage, not just beer, they could be dominating in non-alcoholic categories too. Suppliers should be supporting the development of non-alcoholic divisions with long-term investment and strategic focus. Distributors, meanwhile, need to create entirely separate divisions dedicated to non-alcoholic beverages—complete with dedicated teams, playbooks, and execution strategies tailored to wellness, functionality, and retail nuance. This means more than loading a few extra SKUs on the same trucks—it means designing systems with the same precision, support, and ambition as their beer business.

Together, they could create systems strong enough to make PepsiCo, Coke, or Keurig Dr Pepper pause before shifting distribution—or even acquiring these brands. But right now, the pattern is painfully familiar: the brand gets acquired, and the default move is to pull it from the beer network. Why? Because distributors haven’t built the reputation or infrastructure to retain it, and suppliers haven’t made a convincing case for staying put. It’s not just about distribution muscle—it’s about trust, strategy, and execution.

The stakes are high. U.S. beer production and imports declined by 5% in 2023, and beer shipments were on track to fall below 200 million barrels for the year—the lowest in a quarter-century. Meanwhile, Gen Z drinks about 20% less than Millennials did at the same age, and alcohol consumption among adults under 35 has dropped from 72% to 62% over the past two decades.

Beer isn’t what it used to be. Non-alcoholic beverage brands represent not just a growth opportunity—but a future-proofing strategy.

Section 1: Acquisitions That Sparked the Pattern

- PepsiCo acquires Poppi (2025) – $1.95B

- Celsius Holdings acquires Alani Nutrition (2025) – $1.8B

- Keurig Dr Pepper acquires 60% of GHOST (2024) – $990M

- PepsiCo acquires Rockstar Energy (2020) – $3.85B

- Dr Pepper Snapple acquires Bai Brands (2016) – $1.7B

- Coca-Cola acquires minority stake in BodyArmor (2018), full control in 2021

- Coca-Cola fully acquires Honest Tea (2011), discontinues it in 2022

- Coca-Cola acquires Odwalla (2001), discontinues it in 2020

- Mondelez acquires Clif Bar (2022) – $2.9B

- Mars acquires Kellanova (2024) – $35.9B

- Hershey acquires Dot’s Pretzels and Pretzels Inc. (2021) – $1.2B

- J.M. Smucker acquires Hostess Brands (2023) – $5.6B

These deals made headlines—but for beer distributors, they triggered losses.

Section 2: A Pattern of Mismanagement After Acquisition

Several big beverage companies have struggled post-acquisition:

- Coca-Cola shut down Honest Tea and Odwalla.

- Anheuser-Busch shuttered Hiball Energy and Alta Palla.

- Bai Brands lost momentum after being acquired by Dr Pepper Snapple.

- PepsiCo’s Rockstar purchase has underperformed relative to expectations.

These examples make one thing clear: moving a brand into a larger distribution network doesn’t guarantee success. Sometimes it strips away the brand’s soul.

Section 3: The Legal Headwinds Holding Distributors Back

Beer distributors don’t have the same legal protections on non-alcoholic beverage agreements that they enjoy for beer. While most states have franchise laws protecting beer contracts, those laws typically don’t extend to non-alc products. That means a distributor can spend years building a brand—only to lose it overnight when an acquisition occurs.

New York and New Jersey, for example, have stringent rules: liquor distributors in New York can’t carry mixers or flavored beverages, and beer distributors in New Jersey can’t even sell into supermarkets or convenience stores. These restrictions make it nearly impossible to scale non-alc brands within traditional beer houses.

This patchwork of legislation also discourages long-term planning and investment in non-alc because distributors know they can lose those brands without recourse.

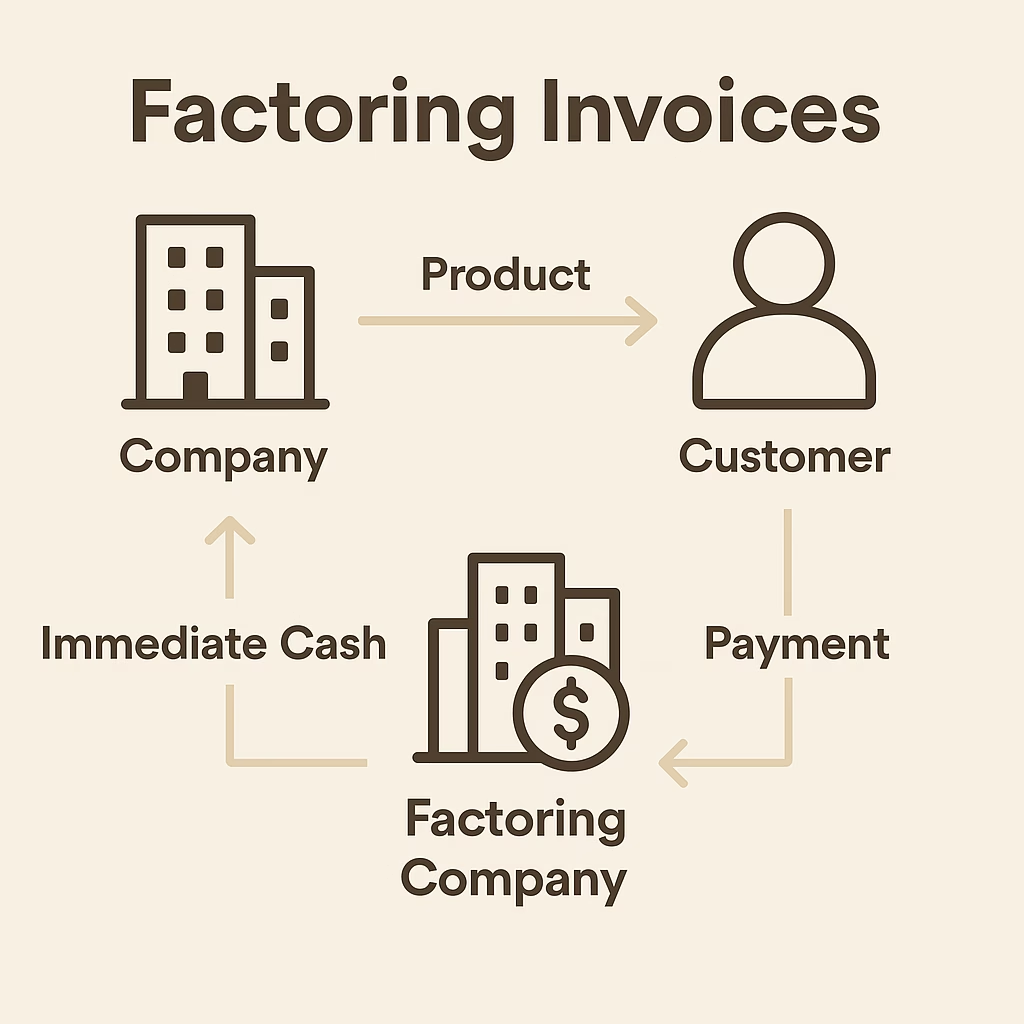

Section 4: Exit Terms Are Built In

When a non-alcoholic brand is acquired, the new owner often has the right—but not the obligation—to remove the brand from its current distribution system. This isn’t automatic. If the acquiring company wants to move the brand, they must exercise the buyout clause in the existing distributor agreement. This clause ensures the original distributor is financially compensated for the time, effort, and resources they invested in building the brand.

But the financial payout doesn’t replace lost sales, lost customers, and lost momentum. And unlike beer, where franchise laws often prevent a supplier from cutting ties, non-alc distribution agreements offer no such protection. It’s easy to leave. And for the acquirer, it often seems easier to pull the brand than to keep working with the current distributor—even when that distributor helped make the brand successful in the first place.

Section 5: The Distribution Systems Themselves Need Work

Beer distributors have some of the most powerful distribution platforms in the world. But to stay relevant—and keep the brands they help build—they need to modernize, diversify, and re-prioritize.

Yes, there are legal headwinds. Yes, non-alc brands don’t fall under the same protections. But there’s more to the story. Distributors and their supplier partners need to build stronger systems that go beyond logistics—systems that prove they can launch, scale, and support these brands long after they become successful.

And it’s not like the Big 3 have set the gold standard, either. Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Keurig Dr Pepper have stumbled after major acquisitions. Snapple, acquired by Keurig Dr Pepper’s predecessor Cadbury Schweppes, saw its relevance decline. Rockstar’s momentum plateaued after Pepsi’s buyout. Even BodyArmor—purchased by Coke—has struggled to deliver the dominance many expected.

So, if the acquiring companies aren’t consistently growing these brands post-acquisition, why not give more consideration to leaving them where they are—especially when beer distributors have built the foundation?

It’s worth asking: with all the trucks, warehouses, relationships, and retail access beer distributors have… why aren’t they considered essential partners post-acquisition? Could it be that they simply haven’t built the non-alc infrastructure that makes them hard to replace?

If the distributor isn’t positioned to retain the brand after it’s acquired, that’s not just a missed opportunity—it’s a self-inflicted wound.

Section 6: Lack of Category Expertise

Non-alcoholic beverages—especially functional drinks, enhanced waters, adaptogenic sodas, and better-for-you teas—require a different approach. These are lifestyle-driven products built on wellness trends, not just refreshment or alcohol replacement. They thrive in wellness-forward aisles and thrive even more when sales reps know how to speak the language of their buyers.

Beer distributors are trained for a different battlefield. They excel at rotating stock, executing displays, and moving volume. But they’re not often equipped with the education or fluency in nutrition, functional benefits, or health-conscious consumers that these brands demand.

Even worse? Many beer suppliers approach these new categories with legacy strategies—like flooding the market or launching with flashy campaigns before the product has even found its footing. That’s the fastest way to kill an emerging brand. A mother buying an adaptogenic soda at a mass-market supermarket and handing it to her kids? It’s the death of cool.

Early adopters want to discover new products—not have them served via a Super Bowl commercial. Traditional marketing plays a role later, once the brand has been built through community, sampling, and cultural momentum. Leading with mass media can backfire hard.

The takeaway: beer distributors (and suppliers) need to invest in learning these categories, not just shipping them. This is a long game. You don’t bulldoze your way to a loyal consumer base. You earn it.

Section 7: Missed On-Premise Opportunity

Beer distributors have longstanding relationships with bars, restaurants, delis, hotels, and campuses—on-premise channels where trends are set and new products are discovered. So why aren’t more non-alcoholic brands breaking through here?

There’s a persistent myth in the industry that bars and restaurants can only serve beer, wine, and liquor. But take a look behind the bar at almost any high-energy venue and you’ll likely see a mini fridge full of Red Bull. Red Bull is the perfect case study in how a non-alc brand can dominate on-premise through clever positioning, strong incentives, and relentless focus.

If Red Bull figured it out decades ago, why hasn’t anyone followed suit? The answer often comes down to creativity—or lack thereof.

Many beer distributors don’t have the playbooks or permission structures to build non-alc in the on-premise space. And to be fair, some state laws prohibit them from giving away product or offering certain incentives. In many states, beer and liquor distributors can’t legally sample, give away merchandise, or even subsidize glassware or signage. That makes the job harder—but not impossible.

This is where bold thinking matters. The right distributor doesn’t just deliver cases—they activate the brand. They find ways to merchandise creatively. They partner with accounts on social media campaigns. They turn bartenders into advocates. That’s how you build relevance, not just presence.

Beer distributors have already invested heavily in refrigerators, coolers, and display units across thousands of locations. They’re in the right places—they just need to use their footprint smarter.

Section 8: The Margin Myth

One of the most common arguments from Budweiser and Molson Coors suppliers is that their own distributors want too much margin to carry non-alcoholic beverage brands. But that’s not quite accurate.

What’s actually happening is this: beer distributors are used to making 20–25% gross margin on their beer portfolio. When they’re asked to carry non-alc brands, they often want 30–35% to make it worth their while. That 5–10% delta becomes a sticking point—not because anyone is demanding it per se, but because beer distributors are conditioned to expect a different margin structure on non-alc beverages than on beer.

Now here’s the rub: those higher-margin expectations often come with weaker, non-binding distribution agreements. That’s where the frustration starts. Budweiser and Molson Coors want their own distributors to take on these brands with lower margins and weaker contracts than they’re used to. It creates tension between supplier and distributor at a time when both sides should be working together to build long-term value.

This also makes it harder for the suppliers to make enough margin themselves—because they’re paying more margin to their distributor while trying to build a category that may not yet have scale.

Do you take margin or cash to the bank? What good is a 25% gross margin if the brand disappears in two years?

Margin matters. But becoming a better, more indispensable partner matters more. You need margin to live—but margin alone is not life.

Section 9: The Culture Problem

Budweiser and Molson Coors have thrown plenty of money at non-alcoholic beverage initiatives over the years—often bringing in expensive talent, launching new internal teams, or greenlighting flashy innovation projects. But many of these efforts fall into the same trap: a culture built on meetings, approvals, hierarchy, and rigidity.

At one major beverage company, Zoom meetings ballooned to include 20–30 people discussing a non-alc brand that was never even introduced to distributors or retailers. The tracking forms looked beautiful. The ideas were polished. But when it came time to launch? Nothing happened. The brand was shut down before it ever made it to market.

The problem isn’t lack of intelligence—it’s the lack of urgency, flexibility, and trust in the people actually doing the work. Some of the best non-alc brands were built by scrappy founders selling product from the back of a van or off a boat. Nantucket Nectars started that way. Honest Tea, too. But when big companies take over, they often substitute creativity with process—and wonder why nothing sticks.

If the culture isn’t built to support speed, risk-taking, and adaptation, the product will never get the chance to thrive. This is where many big beverage companies fail: not in their vision, but in their execution environment.

And here’s the ironic part: many of these teams operate in sleek offices, complete with ping-pong tables, open kitchens, and design-thinking posters on the walls. But innovation doesn’t happen because of office aesthetics. It happens because people are empowered to move fast, fail smart, and keep going.

To succeed in non-alc, the culture has to match the ambition. Otherwise, the brand never makes it past the first slide deck.

Section 10: Why Aren’t Budweiser or Molson Coors Buying These Brands?

If non-alcoholic beverage brands are clearly a growth opportunity—and beer is in steady decline—then here’s the big question: why aren’t Budweiser and Molson Coors making more strategic acquisitions in this space?

Despite having the infrastructure, the capital, and the relationships, they’ve been largely absent from the M&A conversation. While PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, and Keurig Dr Pepper have snapped up brands like Poppi, Rockstar, and Bai, the big beer companies have stayed on the sidelines.

Why?

Some say it’s a lack of strategic focus. Others say they’re hesitant to compete head-on with traditional non-alc giants. Still others point to the constantly shifting internal priorities—every new executive brings a new strategy, and the previous one gets scrapped.

One of the most frustrating things for smaller brands is working with a beer company that launches a non-alc division one year and dismantles it the next. It’s hard to build trust or plan for the long-term when the internal commitment feels like a flavor-of-the-month.

And even when they do invest, they tend to place high-salaried executives at the helm—people who are great at managing big brands, but who have never built anything from scratch. When those execs start holding endless strategy meetings with 30-person Zoom calls and milestone trackers for ideas that never ship, the entrepreneurial spirit dies quickly.

Compare that to the Toms behind Nantucket Nectars, who built a juice empire out of a boat. Today’s meetings have polished pitch decks, impressive dashboards, and gorgeous templates—but almost no urgency. If the product never even gets into a consumer’s hand, what are we doing here?

Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, to their credit, built 20-year plans to diversify their portfolios—and they’ve stuck to them. Budweiser and Molson Coors, on the other hand, have treated non-alc like a side hustle they’re not quite sure they want to commit to.

If they want to stay relevant, that has to change. They can’t just dip a toe in—they have to go all in. Not just by acquiring smarter, but by letting those acquisitions breathe. Don’t suffocate a young brand with red tape. Let it prove itself. Then scale it with muscle and soul.

Section 11: Reimagining the Future—What Distributors Can Do

Beer distributors don’t have to give up their core business to win in non-alc. They just have to rethink their strategy.

- Build dedicated non-alc teams that understand functional beverages, wellness trends, and new retail behaviors.

- Treat non-alc with the same strategic weight as your core beer portfolio.

- Educate and activate your retail partners with real storytelling, sampling, and data.

- Get creative with on-premise—college campuses, delis, boutique gyms, and quick-service restaurants are all wide open.

- Leverage your footprint. You’re already in the accounts. Make every stop count.

The goal is to be irreplaceable. If a brand gets acquired, the acquirer should think twice before pulling it out of your system—not because of a legal clause, but because it would be strategically foolish.

Section 12: What Budweiser and Molson Coors (the Suppliers) Must Rethink

- Hire people who’ve built brands—not just managed them from cushy seats.

- Empower teams with autonomy, accountability, and creative freedom.

- Invest in storytelling and retail activation—not just trucks and logistics.

- Stop using outdated templates and MBA dogma to make decisions. This is not a spreadsheet exercise—it’s brand-building.

- Don’t just talk about diversifying categories—actually do it. Build or buy smart products (not copycats), and when you acquire them, let them breathe.

- Treat your distributors like partners, not vendors. Respect the work they put into growing your brands—and give them strong agreements, fair margins, and real incentive to care.

And above all: don’t believe your own BS. You are not entitled to this market. You have to earn it.

Final Thoughts: The Opportunity Ahead

Other CPG companies would invest in brands, partner with them, and even acquire them—if the beer distribution system could prove it knows how to grow them. This moment presents a huge opportunity for beer distributors to evolve. Rather than waiting for the next brand to be pulled, they can take proactive steps to become the obvious choice—not just for up-and-coming brands, but even for those post-acquisition.

This isn’t about trying to outgun the Big 3—it’s about playing smarter. By developing standalone non-alc divisions, investing in education, hiring category experts, and building flexible marketing playbooks, beer distributors can change the narrative.

Distributors who adapt in this way don’t just keep brands longer—they become harder to replace. And in a world where acquirers are increasingly cautious about post-deal drop-offs, a high-functioning, non-alc-savvy beer distributor could become a strategic advantage worth preserving.

The time is now for beer distributors and their suppliers to build systems that rival or even exceed the Big 3—not just in logistics, but in culture, agility, and execution.

They already have the access. Now, it’s time to focus. If they take the leap, they won’t just keep what they’ve already worked so hard to build—they’ll shape the next generation of beverage growth.

We deal with a few beer distributors that do a nice job for us and also a few beverage/snack distributors. Our beer distributors do not have separate non-alcoholic division, they used too but wanted to get out of the cooler game and chasing payments. Each one does not service very many convenient stores and only a few supermarkets. Most of the beer business in our core market of CT/RI is done in package stores. The up and down the street business is out of their comfort zone and then there is the matter of focus and pressure from the big brands. We have found a way to work with their strengths both on and off premise and it has been very beneficial for us. We continue to deliver to the non-licensed accounts in our area that the beer distributors tend not to enjoy dealing with. Just my two cents