Introduction: What Is a Burning Platform? Most businesses don’t change because they want to. They change because they have to.…

Supermarket and Convenience Store Delays

In an era of overnight success stories and TikTok-viral trends, you’d think that a brilliant new food or beverage brand could make it onto supermarket shelves in a few months. After all, if consumers love something, shouldn’t retailers move fast to meet demand?

Not in the United States.

Here, the journey from idea to shelf can take 18 to 24 months—a painfully long timeline for early-stage companies burning cash, trying to prove product-market fit, and fighting for survival. But this isn’t just about the slow pace. The system itself is broken—filled with outdated practices, red tape, and a bias toward corporate incumbents.

Let’s break it down.

1. Category Review Schedules Are Set in Stone

Most major grocery chains—including Kroger, Walmart, Safeway, and Publix—only evaluate new products during specific category review windows, which happen once or twice per year per category. If you’re a beverage brand, for example, and the review for your category (like water, functional drinks, or energy beverages) just closed, you might be waiting 6 to 12 months just to get a meeting. And that meeting isn’t a guarantee of acceptance—it’s simply a chance to be considered.

Chains that are often viewed as progressive, such as Whole Foods still follow structured review calendars. And once you do get accepted, the internal process of schematics, shelf resets, planograms, and inventory onboarding can add another 3 to 6 months before your product actually hits the shelf. All in, the timeline from pitch to placement can stretch close to two years.

🔒 The problem:

- Trends move faster than reviews. Functional ingredients like ashwagandha, reishi, yuzu, or sea moss might take off in the market, but by the time a category review comes around, the trend could be saturated, replaced, or already peaked.

- Seasonality is missed. If your summer-ready hydration drink gets accepted in December, it might not appear until May or June—causing you to miss critical sales windows or spend more on year-round promotions to keep it alive until the right season.

- Retailers are reactive, not proactive. Category managers often rely on backward-looking data and broad syndicated reports rather than what’s happening on social media, in specialty stores, or on Amazon. By the time something “looks good on paper,” it may be too late to lead the trend.

- International markets are more agile. In Europe, retailers like Sainsbury’s, Waitrose, and Carrefour frequently hold rolling or quarterly reviews that allow small brands to test in-store more quickly. This flexibility gives innovative companies a better shot at growing shelf presence without long wait times.

- Smaller formats aren’t always better. Even smaller regional or natural chains often mimic the annual/biannual review structure of the big players. That means even getting into 25 stores might take a year of waiting—and a year of burning cash.

- There is no fast track. Unless you are a celebrity-backed brand, have massive social proof, or are already selling with velocity in a top retailer, there is no official or structured “early entry” pathway.

Ultimately, the category review structure was built for a slower, more centralized era of consumer packaged goods—not for today’s dynamic, digital-first, rapidly iterating brands.

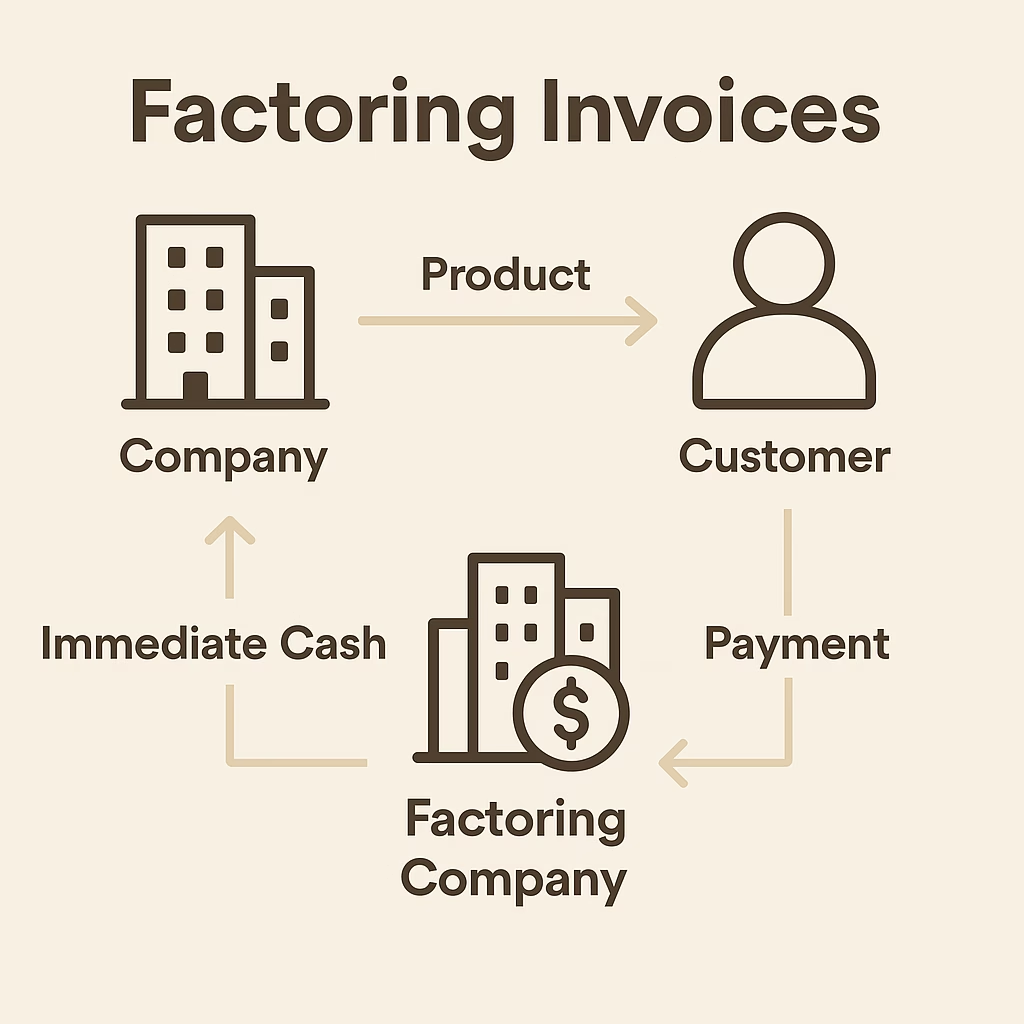

2. Distributors Won’t Touch You Without Retail Commitments

Distributors are supposed to be the middlemen between manufacturers and retailers, but most have reversed the process. Instead of curating exciting new products to present to retailers, they now expect brands to bring retail authorizations to them first—a complete inversion of their original role.

Want to work with UNFI or KeHE? Expect to answer:

- “What chains are already buying you?”

- “How much velocity are you moving in Whole Foods?”

- “Who’s your broker?”

If the answer is “none yet,” you’re likely out of luck.

Even convenience-focused distributors like Core-Mark or McLane—who historically serviced thousands of independent accounts—have adopted the same approach. They want proof of chain acceptance before adding a brand to their catalog. Their logic? If a major retailer didn’t say yes, they don’t want the risk.

The problem is, this creates a closed loop: you can’t get a distributor without retail placement, and you can’t get into retail without a distributor.

So where do emerging brands start? Often nowhere—unless they can:

- Self-distribute locally (which is costly and labor-intensive)

- Work with independent DSD distributors (if they’re lucky enough to find one)

- Pay-to-play through consolidation warehouses or high-commission brokers with inside connections

What’s worse, even when distributors agree to onboard, many require brands to pay onboarding fees, fund promotional allowances, and commit to minimum order volumes—all before generating a single sale.

This system rewards brands backed by venture capital or celebrities, while sidelining some of the most innovative new products in the market.

🌀 What this causes:

- Brands get stuck in distribution limbo, delaying growth.

- Retailers miss out on promising innovation stuck in the pipeline.

- The only winners are brands with deep funding or inside connections.

3. Slotting, Free Fills, and Promo Costs Add Up Quickly — Here’s the Math

For most early-stage food and beverage brands, slotting fees are a rude awakening. You finally get a “yes” from a buyer—only to be told it’ll cost tens of thousands of dollars just to show up on the shelf.

Slotting is the fee retailers charge per SKU, per store, to “reserve” shelf space. It’s meant to offset the risk of onboarding new products and cover resets, system entry, and inventory holding costs. But in practice, it’s a toll booth that favors large, well-funded brands and squeezes out the innovators.

Let’s walk through two examples side-by-side so you can see the impact of what might seem like a minor difference—just $100 per SKU per store:

💵 Slotting Fee Comparison: $150 vs. $250 per SKU

Scenario:

- 100 stores

- 3 SKUs

- Two different fee scenarios: $150 and $250 per SKU per store

| Fee per SKU/Store | Slotting Total |

| $150 | 100 stores x 3 SKUs x $150 = $45,000 |

| $250 | 100 stores x 3 SKUs x $250 = $75,000 |

✅ That’s a $30,000 difference—just from a $100 increase in slotting fees.

And keep in mind: Some chains charge $300–$500 or more, especially in competitive categories like beverages, bars, or refrigerated functional products.

🎁 Free Fills (Intro Inventory You Give Away for Free):

Assuming:

- 1 case = 12 units

- Wholesale cost = $15/case

| Expense Type | Amount |

| Cases Needed | 100 stores x 3 SKUs = 300 cases |

| Product Cost | 300 x $15 = $4,500 |

| Shipping & Freight | Approx. $1,500 |

| Total Free Fill Cost | $6,000 |

📣 Required Promotional Support:

- Intro discounts (10–15%)

- Circular ads or retailer digital media ($1,000–$2,500)

- Endcaps and displays (negotiated, but often $2,500+)

- In-store demos (if allowed): $300–500 per event

Minimum first-quarter promo spend: $7,500–$10,000

📊 Total Launch Cost Comparison

| Fee Type | $150/Slotting | $250/Slotting |

| Slotting Fees | $45,000 | $75,000 |

| Free Fills | $6,000 | $6,000 |

| Promotional Spend | $10,000 | $10,000 |

Total Launch Cost | $61,000 | $91,000 |

🚫 Why It’s Broken:

- A brand could pay $91,000 just to be on shelf at a single regional chain—and that doesn’t include sales team payroll, broker fees, or distributor charges.

- You have to pay this whether your product sells or not.

- Retailers keep the slotting and the leftover inventory if you fail.

- These fees disproportionately hurt small, diverse, and bootstrapped founders who often have the most authentic and innovative products.

And most importantly: consumers lose, because brands that can’t afford to pay never make it to shelf—no matter how good they are.

💡 How to Fix It:

- Retailers should tier slotting fees based on company size or revenue.

- Consider performance-based slotting—pay it after hitting sales benchmarks.

- Launch pilot programs in 10–25 stores with no slotting as a test.

- Retailers should see emerging brands as partners, not fee payers.

4. Retail Buyers Don’t Have Time (or Tools)

Retail buyers are often perceived as gatekeepers, but in reality, they’re overwhelmed operators trying to survive in a pressure-cooker environment. They manage thousands of SKUs across multiple categories, face constant turnover, and are under intense scrutiny from their leadership to hit aggressive performance metrics.

Most buyers simply don’t have the time to answer every email or return every call—especially from unknown or unvetted brands. It’s not personal; it’s survival. Their days are often consumed by:

- Reviewing promotional calendars

- Managing vendor compliance issues

- Addressing out-of-stocks and supply disruptions

- Meeting with category captains (usually large legacy suppliers)

In many cases, their voicemail boxes are full, their inboxes overloaded, and their priorities dictated by those who have the infrastructure—and influence—to execute flawlessly.

To make matters more complicated, technology has changed the game. Retail buyers now have access to real-time dashboards that display:

- Unit sales per SKU per store

- Gross margin by brand

- Promo effectiveness and ROI

- Spoilage, shrink, and return rates

These reports are generated by sophisticated retail analytics systems and syndicated data sources (IRI, SPINS, Nielsen, etc.). The result?

Decisions are now data-first and relationship-second. If a buyer sees that your product doesn’t deliver on velocity or margin—even if it’s promising or “on trend”—they’re less likely to take the risk.

And if they do give you shelf space and your product doesn’t move fast enough, the system flags it for discontinuation. It’s automated. The buyer may like your brand, but the algorithm says no.

This combination of time scarcity and real-time performance pressure means most buyers will only engage with brands that are:

- Brokered by someone they already trust

- Already performing well in a comparable retailer

- Backed by data or guaranteed promotional support

In other words, the new rules of engagement often exclude startups who may not have data, but do have innovation.

📉 Why it fails:

- Great brands get overlooked due to data lag or poor visibility.

- Buyers trust old relationships over new opportunities.

- The industry becomes risk-averse, not trend-responsive.

5. The Onboarding Process is a Maze

Let’s say you clear every hurdle and get the “yes” from a retail buyer. You’re still months away from hitting shelves. Why?

Because onboarding involves:

- Legal review and contract negotiations that can take weeks

- Vendor agreements that must be signed and approved by both sides

- Proof of liability insurance with specific coverage and naming the retailer as additionally insured

- Product data entry into the retailer’s system (ingredients, nutrition, allergens, certifications)

- Third-party compliance checks for label accuracy, UPC integrity, and case packaging

- EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) setup for order processing, invoicing, and payment

- Routing instructions and delivery window confirmations with your distributor or 3PL

- Planogram and schematic integration to place your product in the right shelf set

- Warehouse onboarding, including pallet configuration, SKU case packs, and temperature specs if applicable

Each of these steps requires time, attention, and often coordination with your co-packer, legal team, designer, broker, and distributor. A delay in any one area—such as a missed insurance certificate or a UPC typo—can push your timeline back weeks or even months.

Many retailers also conduct internal reviews for each new vendor. These can include credit checks, background vetting, and compliance audits—all of which are routine for them, but resource-heavy for small brands.

For large brands with full teams, this is just another Tuesday. For small brands, it’s a gantlet of forms, phone calls, waiting games, and system incompatibilities.

🗂️ Consequences:

- Brands lose launch momentum.

- Retailers suffer out-of-stock or launch delays.

- The process favors companies with entire departments to manage compliance.

- Small brands often burn cash and energy simply navigating the system, before a single product hits the shelf.

- Brands lose launch momentum.

- Retailers suffer out-of-stock or launch delays.

- The process favors companies with entire departments to manage compliance.

6. Retailers Prioritize Safe Bets

New brands are risky. They might taste amazing and have a mission-driven story, but if the packaging is unfamiliar or the consumer education isn’t there, retailers fear slow turns and dead inventory.

That’s why shelf space continues to go to:

- Line extensions of legacy brands

- Consolidated brand portfolios

- Venture-backed brands with pre-funded promotions

Retailers want predictability. And the legacy giants—Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Dr Pepper Keurig, and Frito-Lay—deliver that predictability, not just in volume, but in systems, execution, and most importantly: rebates.

💸 How rebates work:

These CPG giants offer retailers substantial performance-based financial incentives, such as:

- Guaranteed margin protection: If the item underperforms, the brand reimburses the retailer.

- Scan-down rebates: A per-unit rebate paid to the retailer for each unit sold during promotional windows.

- Off-invoice discounts: Price reductions applied directly to the invoice, reducing the retailer’s upfront cost.

- Quarterly volume incentives: Bonuses paid to retailers who hit certain volume thresholds.

These financial tools mean retailers don’t carry the same risk for new SKUs from Big 3 companies as they do for emerging brands. Even if a new soda flavor or snack variety doesn’t perform, retailers are often protected through rebate programs.

🧠 What else is involved?

- Category Management Power: These companies often serve as category captains. That means they help retailers build the actual shelf sets, determine the ideal mix of products, and “recommend” what should be added or removed—typically favoring their own new launches.

- Merchandising Control: They employ large field teams and merchandisers who ensure product placement, replenishment, shelf cleanliness, and promotional compliance. Their items are more likely to be stocked correctly and visually prominent.

- Marketing Muscle: National ad campaigns, loyalty program tie-ins, and retailer-specific co-marketing efforts drive awareness and support new product introductions.

- Data Access: These companies often have access to enhanced POS data and real-time retail analytics, allowing them to adjust quickly and demonstrate their value through granular metrics.

🧊 What this does:

- Gives the Big 3 fast-track access to shelf space.

- Allows them to test innovation at retail without real risk.

- Pushes emerging brands to compete with no financial buffer, higher costs, and lower leverage.

- Crowds the shelf with safe bets, even when those categories are flat or declining.

- Slows innovation by creating a system that favors muscle over merit.

- CPG innovation shifts to DTC first—not retail.

- Shelf space becomes predictable and boring.

- Chains lose the opportunity to lead trends instead of follow.

- Emerging brands are held to a higher standard without the tools, leverage, or protection the Big 3 enjoy.

- CPG innovation shifts to DTC first—not retail.

- Shelf space becomes predictable and boring.

- Chains lose the opportunity to lead trends instead of follow.

7. Velocity Expectations Are Unrealistic

You fought your way onto the shelf. You paid the fees, did the demo, ran the ads—and still, after 90 days, your product is marked for discontinuation. Why? Because your velocity per store per week wasn’t high enough.

Most retailers want 1–2 units per SKU per store per week at a minimum, even for brand-new products.

But here’s the truth: some brands just aren’t ready for the big time yet. That doesn’t mean the product isn’t great or the team isn’t talented—it just means the infrastructure, velocity history, brand awareness, and retail execution support may not be in place to meet retail expectations yet.

Approaching a supermarket chain or convenience store distributor prematurely can be a costly mistake. Timing matters. Big chains don’t want to “test and see.” They want proven products that move. If your product hasn’t built up traction in independents, online, or regionally, jumping straight into a chain can lead to failure.

Retailers expect you to walk in ready to:

- Execute a flawless launch

- Fund multiple promotional windows

- Drive volume immediately

- Handle replenishment and logistics at scale

Without a strong foundation and proper timing, even great brands will flounder.

⏳ Why that’s harsh:

- There’s no time to develop brand loyalty.

- Your first 60 days could coincide with weather events, competitor promos, or inventory issues.

- You don’t just lose the retailer—you lose credibility with others.

- Many brands get one shot—and if they’re not ready, that door may not open again.

8. Broker and Distributor Biases Hold Back the Industry

Many brokers only work with brands that can pay monthly retainers ($5,000–$10,000/month) plus commission. On paper, this is supposed to guarantee your brand gets attention. But the reality is very different.

Even when you’re paying them, most brokers simply don’t have the bandwidth, training, or financial incentive to build a brand from scratch. Their teams are stretched thin, and their focus is naturally pulled toward larger, more established accounts—the ones that generate volume and require less effort. Building an unknown brand takes creativity, persistence, and a lot of education—and most brokers aren’t structured to deliver that level of service.

Worse still, most brokers don’t actually “sell”—they introduce and inform. The heavy lifting of pushing the sale, generating store-level pull, and merchandising is often left to the brand or forgotten entirely.

Distributors are no better equipped. Large national players like UNFI, KeHE, Core-Mark, and McLane are not true sales organizations. They are logistics machines with warehouse networks, delivery trucks, and thousands of SKUs to manage. Their salespeople—if you can call them that—are often just glorified account managers overwhelmed by daily problems.

A UNFI executive once told us bluntly:

“Damned if I know. We don’t actually sell anything. We make more money from our advertising programs. When my salespeople go into a typical store, they’re berated by complaints: the order was late, we were out of stock of X, I’ve got broken merchandise in the back you need to give me credit for… How do they have time to sell anything but their top lines?”

This is the reality across the board. Most distributor reps are buried in operational chaos and triage customer service, not selling. They’re constantly dealing with:

- Late or incorrect deliveries

- Missing credits or damaged goods

- Out-of-stock items

- Planogram resets

- Angry store managers

So despite you paying for ad programs, billbacks, discounts, and trade incentives, your brand is often buried under the noise. Unless your SKU is already moving or is backed by a chain mandate, it won’t get any meaningful attention.

And let’s not forget: distributor margins are razor thin. They survive on scale and velocity. They simply don’t make money on small brands. The math doesn’t work. So they do the bare minimum, unless your brand is in their top 10 or part of a portfolio that brings value across multiple categories.

🚫 The Result:

- Startups pay retainers and fees but get minimal attention.

- Retailers only see what distributors feel like pushing.

- Innovation dies before it even reaches the shelf.

- The system favors safe bets and ignores bold ideas.

- Distributors and brokers get paid—whether your product succeeds or not.

9. E-commerce and TikTok Move Faster—So Why Can’t Retail?

While Amazon sellers can technically go live in 48 hours, the truth is that getting a new brand properly set up on Amazon takes a lot more time, effort, and patience than most people realize. Between registering your brand, setting up logistics through FBA (Fulfilled by Amazon), optimizing your product listings, handling images, keywords, A+ content, reviews, and running PPC campaigns, the process can feel like a full-time job.

It’s not easy—and it’s certainly not instant—but compared to traditional retail, it’s still much faster and allows full control over your brand, pricing, and presentation. You don’t have to wait for a buyer to approve you, a schematic reset, or a category review cycle. You simply build, optimize, and launch.

And TikTok? One video, one influencer, one moment of virality—and you can sell out overnight.

Meanwhile, brick-and-mortar retail moves at a glacial pace. It can take 18–24 months just to be considered for a shelf spot. Even then, execution delays, schematic timing, onboarding bottlenecks, and bureaucratic red tape add months more.

While exact figures vary by category, recent studies show that around 61% of U.S. consumers begin their product searches on Amazon, while only 49% start on Google—a dramatic shift from just a few years ago. Among Gen Z and Millennials researching food and beverage products specifically, Amazon and TikTok have become go-to sources for product discovery, reviews, and pricing comparisons.

The irony? Retailers are losing ground to e-commerce precisely because they can’t move faster. And when they do try to onboard viral brands, the lag time often kills the trend. It can take 18–24 months just to be considered for a shelf spot. Even then, execution delays, schematic timing, onboarding bottlenecks, and bureaucratic red tape add months more.

The irony? Retailers are losing ground to e-commerce precisely because they can’t move faster. And when they do try to onboard viral brands, the lag time often kills the trend.

10. Why It Works Better in Europe and Canada

In Canada and parts of Europe:

- Slotting fees are lower or regulated.

- Category reviews happen more often.

- Government export programs support small brands entering retail.

- Smaller chains are more agile and willing to test new products without massive volume commitments.

For example, in Canada, many regional retailers like Longo’s or Save-On-Foods have programs to feature emerging local brands, and slotting fees are often negotiated—or waived entirely—for first-time suppliers. In Germany, chains like Edeka and REWE allow store-level decision-making, meaning small brands can begin in a few locations and expand if successful.

In the U.K., supermarket chains such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s often hold quarterly category reviews, not annual ones. They also engage in smaller, faster retail trials and invest in incubator programs that give startups shelf space and marketing support.

The EU also supports exporters with initiatives like COSME (Competitiveness of Enterprises and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises), and Canada’s AgriMarketing Program helps offset the cost of trade shows and international promotion.

The result? A more dynamic, flexible system that allows innovation to flow faster and more affordably.

This is why many U.S. brands launch internationally first, then return to the U.S. once they’ve built momentum abroad—often with better pricing, more experience, and stronger marketing assets., then return to the U.S. once they’ve built momentum abroad.

What Retailers, Distributors, and Brands Can Do to Fix It

💡 For Retailers:

- Add rolling category review slots for new brands. Don’t make a brand wait 6–12 months to be reviewed. A more agile and responsive review process encourages innovation and allows retailers to keep up with consumer trends.

- Create emerging brand incubator shelves in-store. Dedicate space for early-stage products and promote them with in-store signage and digital support. This low-risk model allows testing without overcommitting shelf space.

- Reduce or waive slotting fees for brands under $2M in revenue. These brands typically don’t have VC backing. Lowering or eliminating slotting helps level the playing field and encourages more diverse product offerings.

- Offer pilot programs with shared data and feedback. Help brands improve through trial—not penalties. Collaborating with new vendors can build long-term loyalty and category growth.

💡 For Distributors:

- Offer regional or limited-time onboarding for promising small brands without requiring major retail commitments. Allow brands to prove themselves with velocity and execution.

- Create a clear, transparent path to distribution. Let brands know what it takes to get listed, and provide a checklist or timeline so they can plan accordingly.

- Re-invest in discovery and curation teams. Many distributors have eliminated brand development departments. Bringing those teams back—or outsourcing them to brokers or consultants—can improve product diversity and relevance.

- Stop relying solely on large brand rebates and promos. Balance your portfolio with emerging brands that excite buyers and consumers, and structure incentives to reward their growth.

💡 For Brands:

- Focus first on velocity and execution in independent retailers and small chains. These wins build credibility and create a foundation for larger opportunities.

- Use DTC (direct-to-consumer), Amazon, TikTok, and social proof to build traction and gather data. Share that traction with retail buyers and distributors as evidence of consumer demand.

- Don’t wait for retail buyers to validate your product. Control your narrative by building brand awareness and a loyal customer base. Retailers are more likely to say “yes” when you walk in with proof.

- Be realistic about timing and scalability. Just because you can produce the product doesn’t mean you’re ready for national retail. Focus on learning, refining, and growing smart—not just fast.

The system isn’t just slow—it’s strategically flawed. The very process meant to ensure quality, consistency, and customer satisfaction has instead become a barrier to innovation, a toll booth for progress, and a time sink for entrepreneurs.

It’s time to modernize how we bring food and beverage products to market. Not just for the sake of the brands—but for the sake of the customers who deserve better, faster, healthier choices.

Final Word: The System Isn’t Just Slow—It’s Failing Innovators

The U.S. retail system for launching food and beverage products is not just outdated—it’s structurally broken. The very process that’s supposed to help consumers discover better products is riddled with inefficiency, gatekeeping, and favoritism toward large corporations.

Slotting fees, rigid review calendars, overloaded buyers, undertrained brokers, and margin-obsessed distributors all contribute to a hostile environment for emerging brands. The irony? These are the same brands that are often the most innovative, most mission-driven, and most aligned with what today’s consumers actually want.

We’re not saying retail should abandon process or caution—but it must evolve.

Retailers should rethink the value of agility. Distributors should rediscover the role of partnership. And brands must stop waiting to be picked and start building their own momentum, proving they belong on shelf by owning their story and their consumer.

There’s a smarter, faster, fairer path forward. It starts with acknowledging that what worked in the past no longer works now. If we want to keep shelves exciting, competitive, and relevant, the system must open up—not slow down.

At Cascadia Managing Brands, we’re not just navigating this broken system—we’re actively helping brands outsmart it. From go-to-market strategy to sales execution, we help turn high-potential products into high-performing brands.

Let’s build something better—together.

Need help beating the system—or building a smarter route to market?

Cascadia Managing Brands has spent 30+ years navigating the mess. We know how to get your product retail-ready—and shelf-worthy. Let’s talk.